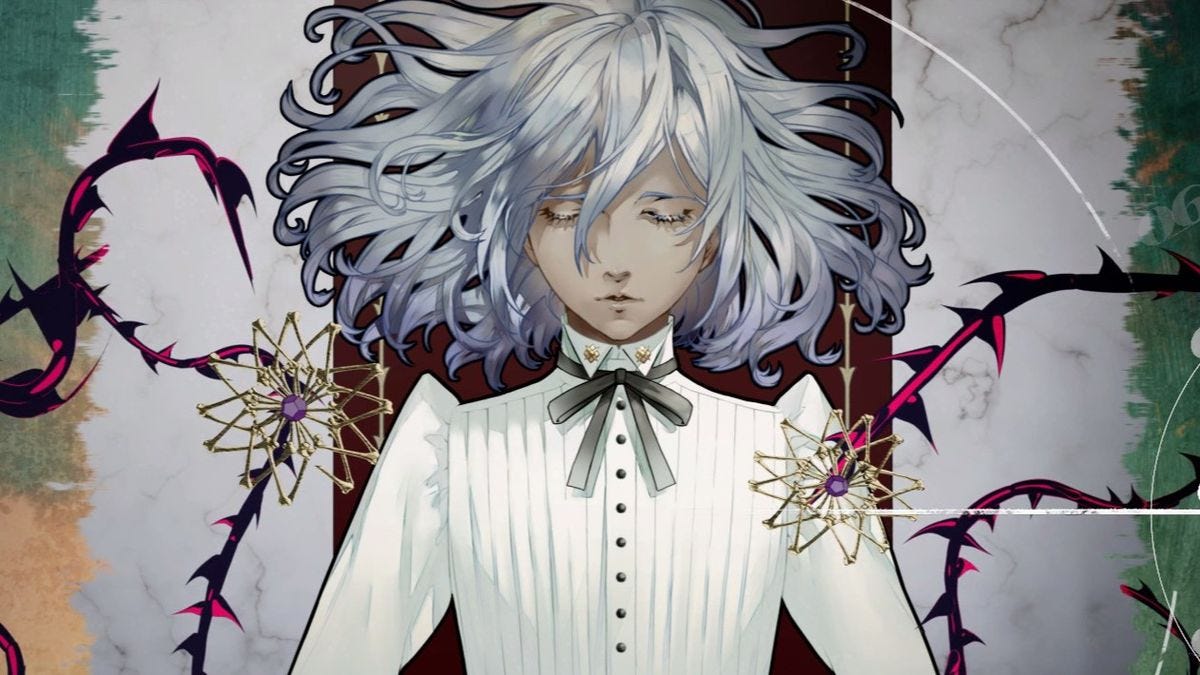

80 hours and almost three months later, I’ve finally beaten Metaphor: ReFantazio. It’s beating a dead horse to say this, but it’s an incredible experience. It’s an epic tale of the power fantasy and fiction can have in inspiring a better world with a deep and likable cast of characters to become allied with in the fight for hope against tyranny. In many ways, it’s exactly the type of game we need in this moment. A reminder that heroism is often never done alone and it will take all of us to stand together to free the world of the kind of evil that would abuse power to keep the downtrodden down.

I’m very glad I played it. I’m also so glad it’s over because for the last 30 hours, I was waiting for the credits to roll but they just never did. Much has been said about video games as an art form. How unique they are amongst storytelling mediums. No other medium lets you interact with it on the scale that games do and this often enhances narratives. Games aren’t passive, you aren’t experiencing the story from the outside, you’re in it. What happens to the main character by extension happens to you. Their actions are your actions, their consequences are your consequences. It’s that unique connection between the player and the game that so often enhances a story that would otherwise be experienced from afar.

But there’s one thing that games have to worry about that other storytelling mediums do not. Game design. How does the game play? The mission design, the structure, whether it’s open-world, whether there are side missions or collectibles, how the player interacts with the world and other characters, etc. Every single thing the player will ever do while playing is determined by this. That also means everything they do while experiencing the story is determined by the game design. And sometimes the game design gets in the way of the story.

Added to Questlog

Much has been said over the years about the stilted nature of open-world story design. But this is my blog so I’m gonna say more. There’s a running joke about open-world games that the hero prophesied to save the world is off fishing or helping some random farmer find their lost keys. It’s a funny joke rooted in something very real.

Open-world games by their very nature get in the way of their storytelling. When you design you’re game around the player being able to advance the story on their own time while they go off to do side activities, the story becomes stilted.

In Skyrim, you’re on a quest to save the world from a dragon prophesied to destroy the world. Those are pretty big stakes. But because the game is open world you could play for 100 hours without making any progress in that quest. The fate of the world is in your hands but there’s practically no agency. At any point in the story, you can just put it on hold indefinitely.

In Cyberpunk 2077 (one of my favorite games of all time), you’re on a mission to get a chip out of your head before it kills you. But because it’s open-world you can play for dozens of hours without ever worrying about the fact that you have a limited amount of time to live. It’s an incredible story but because of the way you experience it, it doesn’t have the impact it could have otherwise. For all the added weight that actually playing as this character gives the narrative, being able to stop and start it at will to do side quests takes a lot of that weight away.

I can go on and on listing open-world games and how their design belies their narrative. I’m not gonna do that because I know you’re here for Metaphor. I’ll get to that soon I promise. I just want you to know that what I’m talking about isn’t exclusive to Metaphor. It’s not even a new phenomenon. And it’s not just open-world games and RPGs that are guilty of it.

Ludo-something something

Do you have a moment to talk about our lord and savior Ludonarrative Dissonance? I’m sure you’ve heard this term before, probably from Neil Druckmann as he sniffed one of his own farts.

Ludonarrative dissonance is the pretentious term for when a game’s narrative and mechanics are incongruous. It’s not really pretentious, but I understand I’m talking to gamers on the internet, so I've got to play to the crowd. The open-world problem counts as ludonarrative dissonance as well but for this segment, I want to focus on other games.

Nathan Drake is a charming, likable guy in the narrative. In the gameplay, he indiscriminately slaughters thousands of people. This guy has a bigger kill count than John Wick, James Bond, and 80s Schwartzeneggar combined. The Last of Us 2 is a game about how violence is wrong and it lets you slaughter the remaining population of post-apocalyptic America with a smile on your face. And just so I’m not completely picking on Naughty Dog, the Tomb Raider reboot has Laura completely traumatized at having to kill someone in self-defense and then lets you play like you‘re Rambo.

Once again I could go on and on listing games that suffer from this. It might seem like it’s an inescapable problem for games since they have to offer the player some form of friction and that often means enemies to kill. But lots of games don’t.

Horror games often feature gameplay that completely operates within the normal bounds of their story. Even when you’re roundhouse kicking Spanish villagers infected with RFK Jr’s brainworm in Resident Evil, it doesn’t differ from the narrative. Spec Ops: The Line wants you to mow down enemies because it wants to tell you how terrible you are to derive enjoyment from that. Even all the war crimes you do in Call of Duty make sense narratively. That’s not even to mention all the non-violent games that don’t suffer this.

Basically, the point I’m trying to make here is that many, maybe even the majority of games, certainly the majority of AAA games, suffer narratively because of their gameplay. The one aspect that strengthens the weight and audience attachment to a story is just as often the thing that unravels it. It’s been a thing since video games were invented and most likely will be a problem for as long as they make video games. It doesn't make games less of an art or worse than other forms. It’s just a unique problem that they have.

Of course, everyone is different and so this may bother some people while some people won’t care. For some, it may vary from game to game, story to story. Some stories may be strong enough for it not to matter, others it may become an annoyance.

And that finally brings me to Metaphor: ReFantazio, I game that I really liked, loved even, and yet…

The Age of New King Draws Nearer

I hate this goddamn fucking in-game calendar! It’s a nice novelty at the beginning but the more the story escalates the more it gets in the way. Every single story beat in this game is beholden to this thing. And on top of that literally everytime you complete something that moves it forward you have to sit and watch the exact same little cutscene. Every. Single. Time.

Time marches on and the age of a new king draws nearer. It’s fun the first time you see it but you have to see it at the end of each in-game day. There are around 100 in-game days before the point of no return. So you have to watch that 10-second clip 100 times. It never changes. At first, it’s nice. Very quickly it becomes annoying. By the time you’ve reached the end of the game, it’s like Chinese water torture. It’s an overbearing irritation that wastes time and grates your nerves so much that you question if you like the game as much as you think you do. It is ironically a perfect Metaphor for the calendar system itself.

Metaphor has the same problem that every open-world game has. The story is not allowed to resolve on its own momentum. Except in Metaphor, it’s not because of the player dictating when they move on to the next beat, it’s the game design itself roadblocking the player from getting on with it.

Everything in the game is tied to the calendar system. Every major action in the game moves the clock forward. Traveling to a location, doing a dungeon, bonding with your party members, even menial things like sweeping your airship or reading. Each story quest needs to be completed by a certain in-game day. Some side quests also have a deadline.

Because the game is essentially designed around this system, the game always forces you into it even when it makes no goddamn sense story-wise.

Early in the game, it’s fairly well-integrated and diegetic. The story will see you and your companions on a quest to hunt down a wanted criminal in order to gain favor with the people of the kingdom in the competition to be King. So it makes sense that the game gives you 30 days before you have to do this.

Within those 30 days, you can do side quests to level up and increase your bond with people to unlock new abilities and strengthen your current ones. Since narratively the deadline for this is a set date in a competition, it all makes sense.

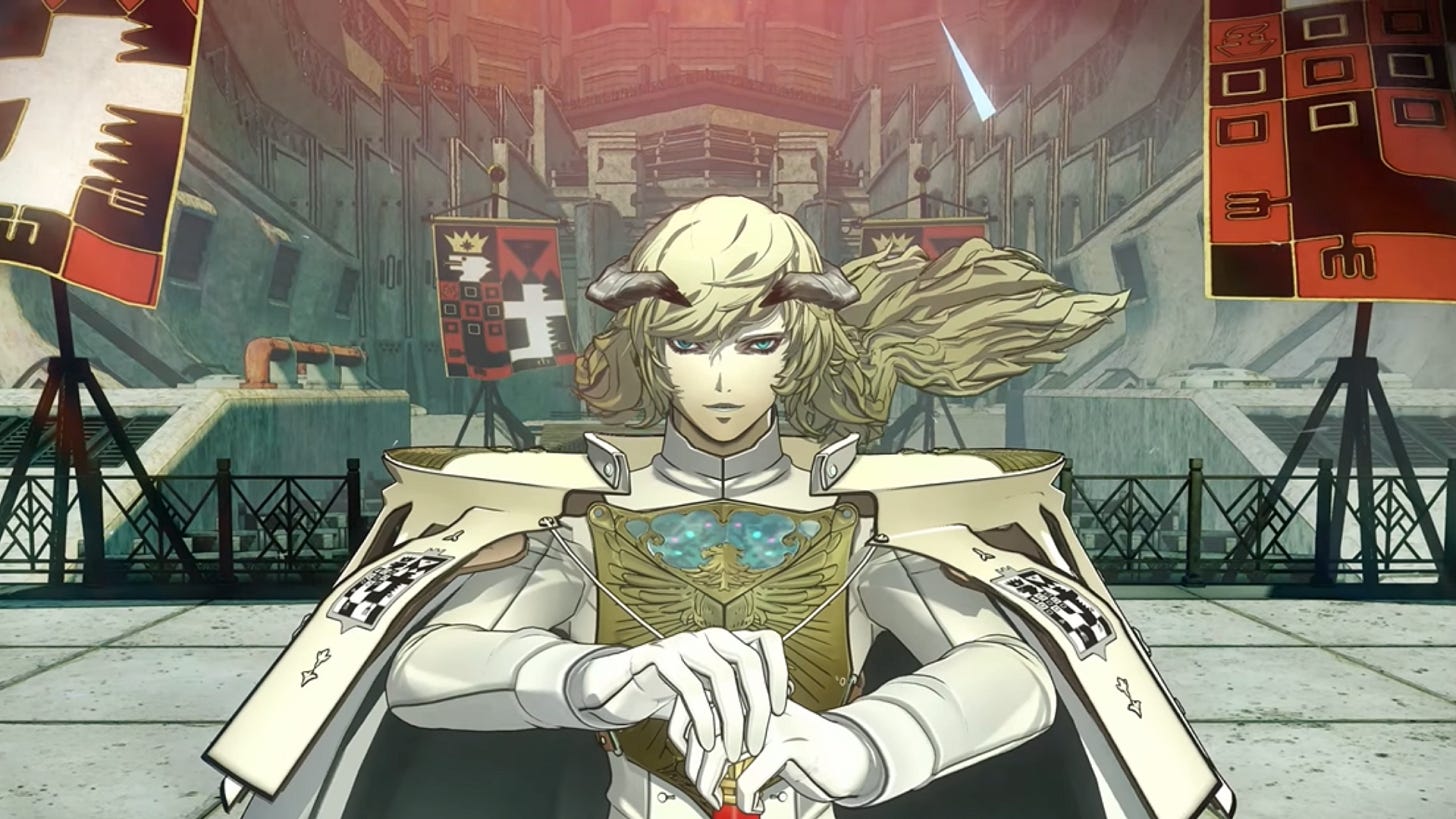

But the further the game goes on, the less sense it makes for your character and their party to do anything other than immediately do the next story quest. With each passing story beat, the villain gets deadlier and more evil, the stakes get higher, and the quest to save the world more urgent. Yet the game design remains the same. You have 30 days to muck about before you move on. The game insists that the age of a new King draws nearer every time you sleep and that’s true, except logically that new King is the main antagonist Louis since you’re off biding your time right after he did the most dastardly thing you’ve ever seen.

I don’t want to give away spoilers because the story is genuinely very good and deserves to be experienced so I’ll try to be as vague as possible.

There’s a moment late into Metaphor, and when I say late I mean there are still 20-30 hours left, it’s after you’ve already passed the protagonist’s lowest point and are confronting Louis. He activates his evil magic McGuffin that will essentially end the world and challenges you to stop him.

Any writer will tell you this the moment that the hero immediately goes after the villain to have the final showdown. All the narrative momentum is there, leading to the final showdown. The hero had their low point and crawled back from the ashes, the villain’s victory is imminent. This is the climax.

So the game has your party regroup for 30 in-game days to finish off quests and grind a bit before the final dungeon. Absolutely insane. The story is completely cut off at the knees because the game is hell-bent on painting its central design principle of the calendar deadline system. So now at the apex of the story, the game puts the climax on hold so you can do a few side missions and spend days talking to your companions and other friendly NPCs.

It completely deflates the moment. All the momentum the story had is immediately stripped away as soon as the game gives you that 30 days. The story is saying “This is the final battle, this is the moment of truth for our hero, this is when good must prevail”. The game is saying “It can wait”. There are a couple of other moments in the back half of the game like this but none as egregious as this final time.

This is my main problem with Metaphor. This is what keeps it as a 4-star game instead of a 5-star game. As great as the gameplay and the story are, it’s at odds with itself. It’s stuck in limbo. It exists as not quite an open-world game and not quite a linear one. It’s full of explorable areas and optional content but it funnels you to the story through the calendar system. But it also still leaves you with the freedom to do side content. It’s a tight balance that works gameplay-wise but completely cracks the foundation of the story.

It’s not quite ludonarrative dissonance because what you do during the downtime is in line with the characters but having that downtime to begin with is completely antithetical to the story. It also doesn't quite have the same problem open-world games have. Those games have their momentum stunted by the player's own volition. Metaphor doesn’t do that. Metaphor stunts its own momentum.

*Quick Note: I started writing this a few days after I finished Metaphor in February and it’s at this point I stopped to take a break because I was just so burnt out on Metaphor I couldn’t even write about it. It is now April and I’m picking this back up but it’s been so long I’m just gonna wrap it up. Which is ironically what Metaphor struggled with.

It’s frustrating because not only is the story really fucking good but there’s a simple solution. Just ditch the calendar system at a certain point in the game.

Final Fantasy 15 had this figured out a decade ago. That game is open world but guess what they do during the most important story moments? Go on, guess. If you said, they lock the player out of the open world and into a linear story section, congratulations you’re right. Instead of letting their story lose momentum because big moments aren’t being followed up on when they should, they force the players to follow up on them before they go back to the open world. And guess what else, the last few chapters in Final Fantasy 15 are completely linear because the devs knew that stretch of the story should not be broken up.

So Metaphor is a game that I loved with a story that I loved that by the time I got to the end I felt relief more than anything. Relief that it is finally over because it refuses to end because when it comes to its natural conclusion, it decides that actually, the villain will wait for you for 30 days. How nice of him.

Video games are the most unique form of art. No other storytelling medium has the tools that games do. It is my firm belief that for the most part, those tools strengthen the impact the stories have on the audience. But for just as much as those tools do a service to the story, they also do a disservice to them. Sometimes it’s not a problem. Usually, for me, it isn’t but with Metaphor it really bothered me. Because I loved this game. I loved these characters. I loved this story and I’m mad that the game made me get to a point where I was mad at it and just glad to be finished.

And it’s all because of that goddamn fucking calendar system that cuts the story off at its knees. Metaphor is an incredible game with an incredible story and message but its game design does its story a disservice. It’s like if you were watching a really great show and in between the penultimate episode and series finale, there were 15 filler episodes. For a game about the power of fiction, it sure does have a proclivity for completely breaking your immersion and reminding you that you’re playing a video game.

Video games have the power to immerse us in stories like no other medium but they also have the power to make sure we’re always aware that we’re playing a game and we still have content to complete. Metaphor does the former which just makes it so much more trusting when it also does the latter.